Landsraad of Las Vegas Meta

The Treachery Deck and the Four Pillars of Dune

With the introduction of new factions, mechanics, and design ideas, it is natural to ask whether the original 33-card Treachery Deck can be improved. At six or fewer players, the answer is simple: no. When examined through the lens of the Four Pillars of Dune — Cost, Scarcity, Minimums, and Deduction—the original deck reveals itself as a carefully balanced system that supports every style of play at the table.

Cost: Nothing Is Free

The structure of the deck immediately enforces cost. Its composition—five Worthless cards, eight Defenses, nine Weapons, and eleven Specials—ensures that not every card is desirable. Special cards range from game-changing tools like Karama to situational or restrictive cards such as Family Atomics which may sit, unusable, in a player’s hand for most of the game.

If weak or worthless cards did not exist, every card would be worth bidding on, and the blind auction would lose its exhilarating experience of wonder and reward. Cost in the Treachery Deck is not just about spice spent; it is about opportunity cost. Players must decide whether to commit resources to an uncertain reward, knowing that a successful bid may be a detriment in their hand makes the Blind Auction what it is, exciting.

Scarcity: Valuable Options, Not Total Options

Scarcity in Dune is not about limiting the total number of cards, but about limiting access to valuable ones. The presence of weaker and worthless cards preserves this scarcity by diluting certainty. Only a small subset of the deck meaningfully alters the balance of power at any given moment, and that uncertainty is what fuels tension during the bidding phase.

The Treachery Deck is also self-regulating. At slower, more political tables, powerful cards tend to remain in players’ hands, while weaker cards cycle through the discard pile and reshuffle, reappearing in future auctions. At faster, more aggressive tables, powerful cards are frequently expended on win attempts, sending them back into circulation. In both cases, scarcity is preserved not by design intervention, but by player behavior.

Minimums: Preventing Stagnation and Collapse

Scarcity alone would make Dune brittle. Minimums ensure that the game remains playable and dynamic even when players fall behind. The Treachery Deck supports this by maintaining a power curve that allows both strong and weak players to influence the game state.

Too many weak cards cause stagnation: players in strong positions cannot find the tools needed to push for victory, and players in weak positions cannot meaningfully change their fortunes. Too many strong cards remove risk from the auction and disproportionately benefit factions that can buy early, allowing them to deprive others of resources. The original deck strikes a balance that ensures every player, regardless of position, can still affect the game each turn.

Deduction: Structured Uncertainty, Not Luck

Dune is a strategy game without dice. Its tension comes from uncertainty that can be reasoned about, not randomness that must simply be endured. This is most visible in combat.

At its core, Dune combat is governed by a binary weapon system: Poison and Projectile, each with a corresponding defense. This simplicity allows players to track information, infer probabilities, and commit to battle plans with intention. Outcomes are uncertain, but never opaque.

The Lasgun is the sole and deliberate exception to this binary system. While it is fundamentally a Projectile weapon, its interaction with Shields introduces a catastrophic third outcome, mutual destruction. Importantly, this exception does not undermine deduction—it sharpens it.

The Lasgun does not introduce randomness; it introduces risk. Its presence is known, its effect is fixed, and its consequences are absolute. Players can—and must—reason about whether a Lasgun is in circulation, who might hold it, and whether triggering a nuclear explosion is worth the cost. The Lasgun reinforces deduction by punishing careless assumptions rather than invalidating planning.

This distinction is critical. Cards that alter battles after plans are committed—by removing forces, modifying dials, or introducing unforeseen effects—replace deduction with hope. The Lasgun does the opposite: it raises the stakes while remaining fully predictable.

With the original deck size, players can track weapon distribution, anticipate reshuffles (typically around turn four), and time win attempts accordingly. Deduction remains viable. Expanding the deck excessively or introducing too many post-commitment effects erodes this structure, forcing conservative play or reckless aggression, disrupting the game’s natural flow.

What Dune requires is variance with structure, not chaos. The Lasgun exemplifies this philosophy: dangerous, rare, and entirely knowable.

When Expansion Is Appropriate

Ratios are as important as individual card effects. The blind auction depends on risk: too many strong cards eliminate meaningful bidding decisions, while too many weak cards suppress momentum. Maintaining the original ratios preserves the rhythm of the game, ensuring that conflict escalates naturally rather than artificially.

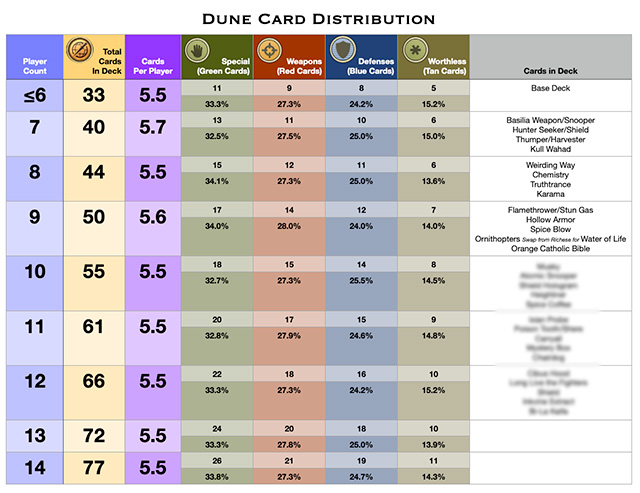

Is there ever a reason to expand the Treachery Deck? Yes—but only when the player count exceeds six. Each additional player increases competition for cards, disrupts scarcity, and compresses deduction. In those cases, additional Treachery cards are required to preserve the Four Pillars rather than undermine them. For those situations, see the Expanded Treachery Deck For Higher Player Counts.

Conclusion

The original Treachery Deck works not because it is powerful, but because it preserves cost, scarcity, minimums, and deduction in careful balance. Altering it without accounting for all four pillars risks will breaking the intangible structure that makes Dune one of the most enduring and strategically rich board games ever designed.